Sombriks Has A Plan

Thoughts on persistence layer and it's solutions

One of the most important things in a modern solution is the data being manipulated. True treasure one can say, or just tables with text inside other can argue.

In this article we'll map our database to be used inside our code. Three times. with distinct frameworks. So we can compare them.

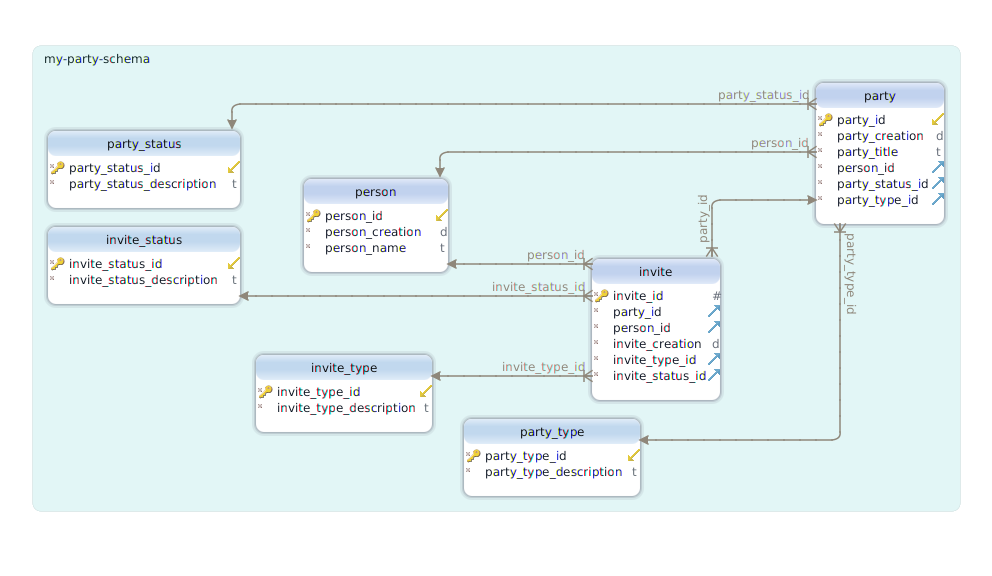

The database schema

First things first, we'll use this database schema:

We will not discuss migrations here, although it's a de-facto standard pattern to manage schema evolutions.

First Challenger: JPA

Java Persistence API is an enterprise java spec quite popular even outside the JEE (now called Jakarta EE! did you saw it coming?) bubble.

The connection configuration, since, we're using spring boot here, is located under src/main/resources/application.properties:

# basic configurations for database access

spring.datasource.url=jdbc:postgresql://localhost:5432/my_party_schema

spring.datasource.username=postgres

spring.datasource.password=postgres

spring.datasource.driver-class-name=org.postgresql.Driver

# Hibernate/JPA should not harm the database schema

spring.jpa.hibernate.ddl-auto=validateOn the JPA world, Our Person class (every table become a class) will look like

this:

package hq.sombriks.sample.model;

import java.util.Date;

import javax.persistence.Column;

import javax.persistence.Entity;

import javax.persistence.GeneratedValue;

import javax.persistence.GenerationType;

import javax.persistence.Id;

import javax.persistence.PrePersist;

import javax.persistence.Table;

import javax.persistence.Temporal;

import javax.persistence.TemporalType;

import lombok.Data;

@Data

@Entity

@Table(name = "person")

public class Person {

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

@Column(name = "person_id")

private Integer id;

@Column(name = "person_creation")

@Temporal(TemporalType.TIMESTAMP)

private Date creation;

@Column(name = "person_name")

private String name;

@PrePersist

public void preInsert() {

if (creation == null)

creation = new Date();

}

}

On this first example, a few notes:

- The

@Dataannotation comes from project Lombok and relieves us from the tedious work of create get/set methods. - JPA can use attribute name as column name. However our database uses

underscores in the table and field names. Do underscores on java identifiers

is a kind of bad practice. Therefore we need the

@Columnannotation so we can rename it. - The

@PrePersistpart is an exotic edge case to help JPA to not try to insert a null value where it shouldn't.

Let's see the Party entity:

package hq.sombriks.sample.model;

import java.util.Date;

import javax.persistence.Column;

import javax.persistence.Entity;

import javax.persistence.GeneratedValue;

import javax.persistence.GenerationType;

import javax.persistence.Id;

import javax.persistence.JoinColumn;

import javax.persistence.OneToOne;

import javax.persistence.PrePersist;

import javax.persistence.Table;

import javax.persistence.Temporal;

import javax.persistence.TemporalType;

import lombok.Data;

@Data

@Entity

@Table(name = "party")

public class Party {

@Id

@GeneratedValue(strategy = GenerationType.IDENTITY)

@Column(name = "party_id")

private Integer id;

@Column(name = "party_creation")

@Temporal(TemporalType.TIMESTAMP)

private Date creation;

@Column(name = "party_title")

private String title;

@OneToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "person_id")

private Person hoster;

@OneToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "party_status_id")

private PartyStatus status;

@OneToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "party_type_id")

private PartyType type;

@PrePersist

public void preInsert() {

if (creation == null)

creation = new Date();

if (status == null)

status = new PartyStatus(1);

if (type == null)

type = new PartyType(1);

}

}One cool thing about JPA is the way it handles foreign keys. Using @JoinColumn

and @OneToOne on a class property which is an entity too will bring it from

database too when we query for it, solving the

select 1 + N problem

One could query for these entities like this:

package hq.sombriks.sample;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertEquals;

import java.util.List;

import javax.persistence.EntityManager;

import javax.persistence.PersistenceContext;

import org.junit.Test;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

import org.springframework.boot.test.context.SpringBootTest;

import org.springframework.test.context.junit4.SpringRunner;

import hq.sombriks.sample.model.Person;

@SpringBootTest

@RunWith(SpringRunner.class)

public class SampleApplicationTests {

@PersistenceContext

private EntityManager em;

@Test

public void contextLoads() {

}

@Test

public void shouldListPeople() throws Exception {

List<Person> people = em.createQuery("select p from Person p", Person.class)//

.getResultList();

assertEquals(8, people.size()); // see sample-data.sql

}

}The EntityManager has this special

query language

and also a criteria query

api (which is a little horrible to read but is strongly typed).

For this case we used JPA with a spring boot project created by spring boot initializr.

Another approach: Sequelize

Sequelize is another popular ORM, widely adopted in javascript/node community.

Like JPA, this is capable of schema generation but, as told before, we're making no harm to the database today.

The connection configuration can be made with this couple of lines:

// db.js

const Sequelize = require("sequelize");

exports.sequelize = new Sequelize(

"postgres://postgres:postgres@127.0.0.1:5432/my_party_schema"

);A model in sequelize looks like this:

// model/Person.js

const Sequelize = require("sequelize");

const { sequelize } = require("../db");

exports.Person = sequelize.define(

"Person",

{

id: {

type: Sequelize.INTEGER,

primaryKey: true,

field: "person_id"

},

creation: {

type: Sequelize.DATE,

field: "person_creation"

},

name: {

type: Sequelize.STRING,

field: "person_name"

}

},

{ tableName: "person", timestamps: false }

);Model definition on Sequelize resembles the JPA way pretty much. Only instead of annotations we have JSON. A lot of JSON.

Another interesting and controversial point is the set of defaults on Sequelize aiming to schema generation. That timestamps property for instance is used to not generate the timestamps columns.

Let's see the Party model:

// model/Party.js

const Sequelize = require("sequelize");

const { sequelize } = require("../db");

const { Person } = require("./Person");

const { PartyType } = require("./PartyType");

const { PartyStatus } = require("./PartyStatus");

exports.Party = sequelize.define(

"Party",

{

id: {

type: Sequelize.INTEGER,

primaryKey: true,

field: "party_id"

},

creation: {

type: Sequelize.DATE,

field: "party_creation"

},

title: {

type: Sequelize.STRING,

field: "party_title"

}

},

{ tableName: "party", timestamps: false }

);

exports.Party.hasOne(Person, { as: "hoster", foreignKey: "person_id" });

exports.Party.hasOne(PartyType, { as: "type", foreignKey: "party_type_id" });

exports.Party.hasOne(PartyStatus, {

as: "status",

foreignKey: "party_status_id"

});Sequelize will always bring mixed emotions to the table, because it's way more opinionated than any other ORM solution.

Also it hits the achievement of make javascript looks more verborragic than java and that's quite an accomplishment.

One could query Parties pretty much like this:

// index.js

const { Party } = require("./model/Party");

const { Person } = require("./model/Person");

const { PartyType } = require("./model/PartyType");

const { PartyStatus } = require("./model/PartyStatus");

Party.findAll({

include: [

{ model: Person, as: "hoster" },

{ model: PartyType, as: "type" },

{ model: PartyStatus, as: "status" }

]

}).then(ret => console.log(ret));You need to tell which related entities will participate to the query.

The query api also has a ton of special operators.

The Bookshelf way

Bookshelf.js is another ORM, but the philosophy is quite the opposite of what was seen in the previous solutions.

It tries as much as possible to keep the bureaucracy away from the works.

It is built on top o Knex.js, a pretty decent query builder.

The database configuration looks like this:

// db.js

const knex = require("knex")({

client: "pg",

connection: {

host: "127.0.0.1",

port: 5432,

database: "my_party_schema",

user: "postgres",

password: "postgres"

}

});

exports.Bookshelf = require("bookshelf")(knex);The Person model looks like this:

// model.js

const { Bookshelf } = require("./db");

const Person = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "person",

idAttribute: "person_id"

});

module.exports = { Person };See the difference?

Bookshelf will only ask for a table name and it's primary key. Other columns will simply be there, so why to bother about them?

Also, it does not uses it's mappings to generate the database schema. Knex already has a pretty decent migration system and Bookshelf recommend that if you want to evolve your database.

Let's see the rest of the models:

// model.js

const { Bookshelf } = require("./db");

const Person = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "person",

idAttribute: "person_id"

});

const PartyStatus = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "party_status",

idAttribute: "party_status_id"

});

const PartyType = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "party_type",

idAttribute: "party_type_id"

});

const Party = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "party",

idAttribute: "party_id",

hoster() {

return this.belongsTo(Person, "person_id");

},

status() {

return this.belongsTo(PartyStatus, "party_status_id");

},

type() {

return this.belongsTo(PartyType, "party_type_id");

}

});

const InviteStatus = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "invite_status",

idAttribute: "invite_status_id"

});

const InviteType = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "invite_type",

idAttribute: "invite_type_id"

});

const Invite = Bookshelf.Model.extend({

tableName: "invite",

idAttribute: "invite_id",

person() {

return this.belongsTo(Person, "person_id");

},

party() {

return this.belongsTo(Party, "party_id");

},

status() {

return this.belongsTo(InviteStatus, "invite_status_id");

},

type() {

return this.belongsTo(InviteType, "invite_type_id");

}

});

module.exports = {

Person,

PartyStatus,

PartyType,

Party,

InviteStatus,

InviteType,

Invite

};Two things shine most there:

- The entire mapping with bookshelf is almost smaller than the

Invite.javaentity mapping. - The relation mapping style is so concise that keep us from get distracted with esoteric configurations.

Finally, query Parties would look like this:

// index.js

const { Party } = require("./model");

Party.fetchAll({ withRelated: ["hoster", "type", "status"] }).then(ret =>

console.log(ret.serialize())

);As seen in Sequelize, we need to express which relations we want to be loaded in each query.

And that's it

There are a lot of tools over the streets offering a better way to tackle the database beast. Some are simpler, some are not.

Maybe i add Go to this challenge, bdr looks pretty decent although Gorm gathers more popularity.

The source code for this blog post can be found here.